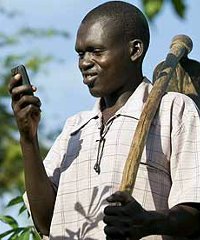

In a recent report, titled Connected Agriculture, Vodafone and Accenture identified 12 opportunities for mobile phone technology to increase agricultural income and productivity. Some of these platforms are already widely used in Africa, while others are still in the early stages of implementation.

1. Mobile payment systems

Mobile payment systems give farmers without access to

financial services an inexpensive and secure way to transfer and save money using their mobile phones. By allowing smallholder farmers to save small amounts of money, receive payments quickly in times of need and pay for agricultural inputs via their phones, mobile payment systems replace costly traditional transfer services and the need to travel long distances to collect funds. They also provide a secure means for employers to distribute wages to agricultural workers, and for governments and NGOs to ensure agricultural subsidies go directly to farmers.

2. Micro-insurance systems

Mobile micro-insurance systems can safeguard farmers against losses when bad weather harms their harvest, encouraging them to buy better quality seeds and invest in fertiliser and other inputs. This can improve productivity and boost farmers’ livelihoods as well as enabling suppliers to expand their market among smallholder farmers. Delivering micro-insurance via mobile avoids challenges with conventional channels that can make insurance expensive. Remote monitoring of weather avoids the need for insurers to make farm visits. With mobile micro-insurance systems, farmers also benefit from quick, secure payouts using money transfer services.

3. Micro-lending platforms

Micro-lending platforms could connect smallholders in Africa with individuals elsewhere willing to provide finance to help the farmers to buy much-needed agricultural inputs. Mobile access to micro-lending platforms provides a free and secure way for rural borrowers to be matched to potential investors and gives existing microfinance providers access to those who need loans the most. Mobile payment records can be used as proof of credit history.

4. Mobile information platforms

Through mobile information platforms, farmers receive text messages with information that help to improve the productivity of their land and boost their incomes. Governments and agricultural support organisations can use the platforms to distribute information about available subsidies and programmes.

5. Farmer helplines

Farmers call a helpline and speak to agricultural experts who can provide answers to agricultural queries. The experts and researchers can use information on the issues raised to improve their understanding of agricultural trends and the challenges encountered by farmers in Africa.

6. Smart logistics

Smart logistics uses mobile technology to help distribution companies manage their fleets more efficiently – reducing costs for farmers and distributors, cutting fuel use and potentially preventing food losses. Devices in trucks communicate with a central hub via machine-to-machine (M2M) connections, providing information on truck movements. Logistics companies supporting input providers, agro-dealers or processors can combine this with information about delivery schedules, loads, trips planned, routes and number of pick-ups to minimise truck movements.

7. Traceability and tracking systems

Mobile technology can be used to track individual food products through the supply chain from grower to retailer. Detailed tracking improves supply chain efficiency and helps smallholder farmers, food distributors and retailers provide the traceability that is increasingly demanded by consumers. It can also help reduce food spoilage. Mobile phones can be used to log the location, quality and quantity of food items at key points in the supply chain. Agents buying products at a farm and workers at distribution centres can use mobile camera phones to scan product barcodes providing details of the items. This information is sent to a central system to give retailers, exporters and distributors a detailed view of product movements. This could help open access to new markets by meeting the requirements of the European Union, for example. Farmers can use the data to comply with certification standards such as Fairtrade and organic, and potentially charge higher prices for produce that complies with such standards.

8. Mobile management of supplier networks

Food buyers and exporters can use mobile phones to manage their networks of small-scale growers and help field agents collect information. Managing large numbers of small farms and growers requires networks of field agents, auditors and technical staff to gather a wide range of information. They carry out farm audits, check the quality and quantity of harvests, and report problems. Keeping detailed paper records for this information is inefficient, can be erratic and can lead to delayed decision making. Equipping field agents with mobile phones improves the supplier management process, providing a reliable, quick and cheap way of creating electronic records in a central database. Field agents visiting farms can use their mobile phones to input data on farmers’ locations, crops and expected yield. Farmers could also use mobiles to send information about their likely harvest date and other key indicators to food buyers and other organisations. Buyers and distributors could use this information to collect fresh food items more promptly and get them to market as soon as possible, reducing food waste and increasing agricultural incomes.

9. Mobile management of distribution networks

Distributors of farming inputs such as seeds and fertiliser could use mobile technology to gather sales and stock data, improving availability for farmers and increasing sales. It can be difficult for companies supplying agricultural inputs to monitor and manage their wide network of rural retailers. Communications and transport difficulties lead to information gaps. Retailers could record sales using a mobile camera phone to scan the barcode, sending this data straight to a central system for analysis. Building up a digital record of sales across a region could help distributors avoid supply gaps. Improved understanding of supply and demand could also help identify new market

opportunities and tailor products to local needs.

10. Agricultural trading platforms

Linking smallholder farmers directly with potential buyers through a mobile trading platform could help them to secure the best price for their produce. Mobile trading platforms could help dealers locate new sources of food when supplies are limited and could help companies fulfil their commitment to sourcing from smaller and more diverse businesses.

11. Agricultural tendering platforms

Online platforms for submitting and bidding on tenders for food distribution, processing and exporting could make the agricultural supply chain more competitive and efficient. There are many distribution, processing and export agents in Africa and poor communications make it difficult to achieve competitive business contracts and tenders. Using mobile phones to access online tendering platforms could help users reach a wider supplier base and promote competition. For example, a food aggregator could advertise a tender to a processing facility. Distribution companies could browse tenders and submit their offers.

12. Agricultural bartering platforms

Mobile could help agricultural workers in rural areas exchange goods and services and improve communities’ livelihoods. For rural people with little or no disposable income, exchanging goods, services and skills with community members is an important part of their livelihoods. Using mobile, people could access an online bartering platform via their mobile phone, significantly extending the network of people to barter with. Users could register their location and the goods, services or skills they are offering, along with details of what they need in return. SMS adverts could be sent to subscribed users, prompting them to respond. Transient agricultural workers could also use the platform to advertise their skills and find work. Farm managers and owners could find workers at short notice, for instance when they need to harvest crops early to stop them being ruined by bad weather. Farmers could barter their surplus food items after a harvest so that food reaches community members in need, rather than spoiling in poor storage.